A “new day” seemingly has come to long-embattled Northern Ireland, a noted columnist/author from that region said in a guest lecture at Tusculum College Sept. 25.

A “new day” seemingly has come to long-embattled Northern Ireland, a noted columnist/author from that region said in a guest lecture at Tusculum College Sept. 25.

“We have crossed the Rubicon and I don’t believe we’ll go back,” said Roy Garland, best known for his weekly columns in The Irish News. Though a Unionist (one who favors continued Northern Irish unity with Britain), Garland has come around to believing that “to be a Unionist does not mean you are against anybody,” he said. “It simply means that you believe you are better off with England than without.”

Old characterizations of Unionists as Protestants and their Nationalist opponents as Catholics no longer are as consistently true as they once were, Garland noted, religious affiliations sometimes mixing within both groups.

As a figure now associated with efforts to cultivate peace and harmony within Northern Ireland, Garland has worked with Catholics and Protestants alike, he said.

His willingness to talk to “enemies outside the gates” has brought him trouble at times, he noted. He showed a slide image of a hand-lettered sign publicly hung in 1995 near his home, declaring that “Roy Garland is a traitor to the people of Drumbeg and Ulster.” That was the same year Garland began writing for the Irish News, a Nationalist publication, though Garland wrote as a Unionist.

Written in at the base of the sign was a statement: “We will never speak to the IRA/Sein Fein,” something Garland had at times done.

Garland’s status as an advocate for harmony was not one he has held all his life. He declared himself a man who has been forced to “rethink everything” he has believed, and who sometimes found, to his surprise, that individuals on the opposite sides of Northern Ireland issues also were going through similar rethinking processes.

Through dialogue with seeming opponents he came around to his current, far less polarized views, he said. “People meeting together and talking together in their humanity can change things,” he told the Tusculum College audience. “If you want to change things, one thing you have to do is identify with the people you want to change and try to lead them.”

Garland began his presentation with a warning that his discussion would at times be difficult for an American audience to follow in detail, partly because of his thick Northern Irish brogue and partly because of the inherent complexity of the issues and history he would discuss.

“Everything is complex in Northern Ireland. Everything,” he said.

Garland grew up in an evangelical Christian home in County Antrim, his father being a part-time pastor in the Church of God denomination that is based in Indiana. For many of his younger years, Garland was little interested in politics, he said, being focused on the spiritual and evangelistic aspects of Christianity.

During that period, however, he heard a visiting preacher at his church propagandizing that the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had “gone communist,” and that there would be “blood on the streets.” To Garland’s young mind this sounded like a prediction of “doomsday,” he recalled.

In later years, when the period known as “the Troubles” brought violence to the streets of Northern Ireland, Garland was sometimes reminded of that preacher’s prediction, he said.

Garland’s older memories of Northern Ireland are of his 1950s boyhood, when “Northern Ireland was largely at peace. There was not much conflict.”

Garland’s father led the Percy Street Church of God in Belfast, and in the early 1960s Roy Garland attended the All Nations Bible College in the London area. His personal focus was largely on evangelical concerns during that period.

Garland’s political awareness and development came gradually, reflective of a similar growing political awareness and factionalism heightening throughout all of Ireland.

Garland’s views were shaped at the same time as the ascension of figures such as Ian Paisley, a clergyman who in the mid-1960s held a service of thanksgiving commemorating the Larne Gun Running of 1914, when loyalists in Ulster, Ireland, who were opposed to Home Rule in Ireland imported guns and ammunition from Germany in order to prepare for armed resistance against it.

Paisley’s commemoration of the Gun Running seemed a “subtle justification of violence,” Garland said.

In 1965, the Ulster Volunteer Force, or UVF, was formed as a modern tribute to the old Ulster Volunteers. The group was concentrated around east Antrim, County Armagh and the Shankill Road, where Garland had grown up, and east Belfast. In May 1966, the UVF declared war on the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and announced it was armed and dedicated to that purpose. A sectarian killing of a Roman Catholic man at the hands of the UVF in June 1966. This attack led to the first leader of the group, Gusty Spence, being arrested and imprisoned. Garland said a second killing also occurred in about the same period. Garland would later become a biographer of Gusty Spence.

The 1966 violence “deeply shocked” the Irish people, Garland said.

As tensions mounted, Ian Paisley, whom Garland described as originally a “street and mission hall preacher,” became increasingly political, Garland said. In mid-August, 1969, Garland attended a meeting of the Ulster Constitution defence Committee, chaired by Paisley. Paisley told of riots and burnings that were under way, and Garland was taken back, he said, to that warning of “doomsday” and “blood in the streets” given by the visiting preacher at his boyhood church. The actual picture of what was going on at the time was not as clear as it then seemed, Garland indicated. In some cases bombs were set off that were blamed on the IRA when in fact they had been planted by opponents of that group who sought to rouse ire against the IRA, Garland said.

In 1969, the Provisional IRA was formed, Garland said. The Provisionals were “militant Nationalists,” according to Garland, who noted that at that same period, he was part of a “paramilitary group” that was preparing for “doomsday.” Though he himself has never owned a gun, he said that the group he was affiliated with was about to begin training Unionists in the use of weapons. He was second-in-charge of that group at the time of his resignation.

In 1970, when Garland attended the Ulster Unionist Conference, he was on the verge of major changes in his approach to Northern Ireland issues. In the middle of 1971, Garland, fueled with doubts about his prior commitments, resigned Unionist groups including the Orange Order. “I became committed to peace-buildng from 1971,” he said.

Garland again became active in the Ulster Unionist Party in the early 1990s and “actively pursued peace and mutual understanding in many contexts,” he said. He became a founding member and joint chairman of the cross-border/cross-community Guild of Uriel, promoting dialogue, mutual understanding and accommodation on all sides, including with dissidents. The Guild is based mainly in County Louth in the Irish Republic.

In recent times he has addressed American degree students in Dublin in their Peace and Conflict Studies course tutored by Brendan O’Brien a noted broadcaster and writer. He was the first Ulster Unionist to address the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation in Dublin in 1995.

Garland is a founding member of the Union Group, a unionist organization promoting an inclusive agenda and seeking healing, reconciliation and growth within Northern Ireland and between North and South and between Ireland and Britain. He has engaged with people at all levels in Northern Ireland and in British and Irish society. He is also active in the Corrymeela Community, a group founded in 1965 to promote reconciliation and peace-building through the healing of social, religious and political divisions in Northern Ireland.

In 2001 Garland published a biography of former loyalist leader Gusty Spence, and has contributed articles to various publications and books. Garland is quoted on the Web site of the British Broadcasting Company as saying that, during the course of his life, he has “re-thought everything. I actually came back to the Unionist party with a different perspective on things, and I believe Unionism is possible without being sectarian.” In a touching visual demonstration of the possibilities of healing between radically divided groups and individuals, Garland showed a slide of a wallet hand-made by Lenny Murphy for presentation to Martin Meehan.

Murphy was a loyalist paramilitary figure from Belfast who was the leader of the so-called Shankill Butchers. Although never convicted of murder, Murphy is known to have killed numbers of people through his own actions, and to have ordered the deaths of more. Garland described him as a man who “killed and tortured Catholics.” Meehan was essentially Murphy’s opposite, a Sinn Féin politician and former volunteer in the radical Provisional IRA. He was the first person to be convicted of membership in the Provisional IRA, and spent 18 years in prison.

Garland is a founding member and joint chairman of the cross-border/cross-community Guild of Uriel, promoting dialogue, mutual understanding and accommodation on all sides, including with dissidents. The Guild is based mainly in County Louth in the Irish Republic.

The day after his Tusculum College appearance, Garland joined Garlands of East Tennessee and from across the country in a gathering of the Garland Family Research Association, a genealogical group promoting knowledge of the family history of the Garlands and sponsoring family gatherings. The group met in Townsend in the Smoky Mountains.

Garland was introduced at Tusculum College by Dr. Donal Sexton, who is retired from Tusculum’s history department.

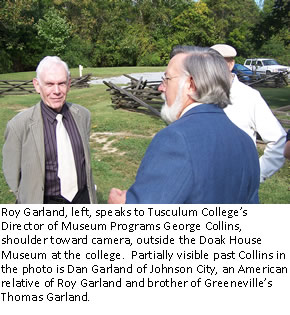

Present to hear Garland were Thomas Garland of Greeneville and his brother Dan Garland of Johnson City, along with various other Garland relations.